Current studies

Language development in monolingual, bilingual, and trilingual children

Children’s language abilities are one of the strongest predictors of their academic success. Children with English as an Additional Language might experience difficulties with English initially, but once their English “catches up”, they do as well as their peers academically (and sometimes even better).

This study explores language experiences and language outcomes in children who are exposed to one, two or three languages at home. It is part of the Q-BEx project, spanning the UK, France and The Netherlands. If you are a parent of a child who speaks English only or English and another language or two, we would like to invite you and your child to participate in our study. Any child can participate as long as they are between 5 and 8 years of age. The study would involve you giving the online consent for your child to participate and filling in an online questionnaire about your child’s language background. We would then meet your child online and do some language and cognitive tasks with them presented as fun computer games. Your child would get a certificate of participation and stickers as a token of gratitude for their participation.

Via this link, you can access more details about our study. The link also includes the consent form, followed by a few questions about you, and then another link to the online questionnaire about your child’s language background.

If you have any questions, please contact us at d.kascelan@leeds.ac.uk.

Assessing Language in Secondary School

Cecile De Cat, Lydia Gunning and Ekaterini Klepousniotou

As children transition from primary to secondary school, the language they encounter becomes increasingly challenging. As the need for independent learning also increases in secondary school, this can lead to pupils who already have difficulty reading, falling further behind their peers. However, there is currently quite limited research on how to identify and help struggling readers of this age.

As children transition from primary to secondary school, the language they encounter becomes increasingly challenging. As the need for independent learning also increases in secondary school, this can lead to pupils who already have difficulty reading, falling further behind their peers. However, there is currently quite limited research on how to identify and help struggling readers of this age.

As part of this project, we have developed a new, online, and automated reading task to identify struggling readers at KS3 and the source of their difficulties. We have integrated the task within a battery of tests which also explores children’s narrative abilities, grammatical competence, and working memory. We are currently rolling out this battery in secondary schools across Bradford, alongside a language background questionnaire for EAL (English as an Additional Language) pupils. This information will allow us to help schools draw up language profiles so they can better target support for their pupils as well as to investigate the impact of deprivation and EAL on language outcomes.

For more information about the project, visit the Centre for Applied Education Research website.

Impact of Covid on Key Learning and Education (ICKLE) (2020-2022)

When primary school children returned to their classrooms in Autumn 2020, they had missed more than a term of usual school provision. This disruption may exacerbate existing inequalities in academic attainment, and potentially create new ones. The ICKLE project focuses on the impact of school closures on pupils who are at the important transition point between reception and Year 1.

Inequalities in children’s learning experiences during the COVID-19 school closures are evident. These include disparities in the support and resources provided by schools, access to technology and study space, and the extent to which parents have been able to support their children. The project will investigate the moderating and mediating effects of these factors on children’s progress in key areas of the Early Years Foundation Stage Profile (EYFSP), including language, literacy, maths, and personal social and emotional development.

Using a quantitative approach and a longitudinal design, the project will recruit a small but representative sample of primary schools in the superdiverse city of Leeds. Demographic data, teacher evaluations of EYFSP scores, and reading levels will be collected in order to follow children’s progress between the point of school closures in Reception, Year 1 Autumn term, and Year 1 Spring term in 2021. In addition, survey data will be collected from schools and parents on home learning provision and engagement during the national lockdown.

If you work in primary education in Leeds and would like to get involved in this study, we are offering schools £100 in exchange for participation in a Covid-secure, GDPR-compliant data sharing process. We are also offering parents a £10 Amazon voucher for completing an online questionnaire about home schooling. Please get in touch with us at ickle@leeds.ac.uk

This project is funded by a UKRI grant to Dr Hannah Nash through the ESRC, with Dr Cat Davies, Dr Paula Clarke, and Dr Matt Homer as co-investigators. For the latest news, go to the ICKLE project website, or follow the project on Twitter

The effects of social distancing policies on children’s language development, sleep and executive functions (2020-2022)

This study examines how changes in sleep, parenting style, social interactions, screen use, and outdoor activities/exercise due to the UK Spring 2020 lockdown affect young children’s cognitive development.

The environment in which children grow up is key to their cognitive development including language and behaviour, and closely linked to their achievement later in life, health and wellbeing. Quarantine measures during the COVID-19 pandemic might have a knock-on impact on parenting styles and children’s sleep, social interactions, screen use, and time spent outdoors.

Our longitudinal study follows a cohort of 600 children aged 8 to 36 months of age, enrolled in an online study at the onset of lockdown, to capture changes in their environment and measure their impact on children’s vocabulary size and executive function.

Dr Nayeli Gonzalez-Gomez, Senior Lecturer in Psychology at Oxford Brookes, who is leading the 18-month-long study, said the research would help future policy makers decide how to reduce the impact on children’s development in the event of further lockdowns. She said:

“Focusing on cognitive development, this project will provide a comprehensive analysis of the effects of social distancing on young children. This is vital for identifying the best ways to support families as we move through the crisis. With further periods of social distancing likely to be imposed in the near future, our findings will identify approaches that mitigate the temporary loss of formal early years’ education, identify those groups most at risk of adverse consequences, and inform policy on how to minimise the impacts of lockdown post-COVID-19.”

This work is being done in collaboration with a team of researchers from Oxford Brookes, Leeds, Warwick, Oxford, and UEA. It is funded by a UKRI grant to Dr Nayeli Gonzales-Gomez through the ESRC. Click here to find out more.

Quantifying Bilingual Experience (Q-BEx)

Cécile De Cat, Draško Kašćelan, Ludovica Serratrice, Sharon Unsworth, Philippe Prévost, Laurie Tuller, Arief Gusnanto

Bilingualism is a world-wide phenomenon, featuring a vast amount of diversity. Researchers, educators and clinicians across the world face similar challenges when it comes to estimating how bilingual an individual is. There is however no consensus at present as to how bilingualism should be measured.

This three-year project, funded by the ESRC, aims to bring a step-change in the measurement of bilingual language experience. It will seek to establish an optimal metric informed by an in-depth review of existing tools and a consensus among researchers, speech & language therapists and educators on what aspects of language experience to index. We will develop online tools to collect the relevant data from children and their families and quantify different aspects of their bilingual experience. We will also develop an objective method to identify early those bilingual children in need of support with their school language, helping practitioners estimate when a child who speaks a different language at home can be expected to have “caught up” with their monolingual peers.

For accessible summaries and infographics presenting our work see here. A list of our published work can be found here.

Completed studies

Paternal Involvement and its Effects on Children’s Education (PIECE) (2021-2023)

Fathers spend more time on childcare than ever before but the implications on children are unclear. Fathers’ childcare involvement should have a positive effect on children’s cognitive and educational outcomes but there is little direct evidence to support this. Research with mothers or parents more generally shows that early parental childcare involvement is critical for supporting children’s development (e.g. Del Bono et al., 2016). Yet paternal pre- or school age care could have different consequences for child development by supporting progression in particular academic subjects, helping to close gender gaps in attainment and/or moderating the known detrimental effects of poverty.

The PIECE study conducted the first longitudinal analysis in England that explored the relationship between fathers’ childcare involvement and their children’s attainment at primary school. Using household data from the Millennium Cohort Survey linked with official educational records of children from the National Pupil Database in England, we explored whether and how fathers’ childcare involvement affects children’s attainment at primary school, and at what stage of the child’s life fathers’ involvement might be most important.

The team have also run a series of forums and discussion groups with fathers, early years’ practitioner and other practitioner organisations to identify the challenges faced, strategies used, support needs and best practice examples for engaging parents in their children’s education.

If you are interested in finding out more, please email h.norman@leeds.ac.uk, visit www.piecestudy.org, or follow us on Twitter @PIECEstudy

The PIECE project is funded by the ESRC secondary data analysis initiative.

- Dr Helen Norman (PI), Leeds University Business School

- Dr Jeremy Davies (Co-I), The Fatherhood Institute

- Professors Colette Fagan and Mark Elliot (Co-Is), University of Manchester

- Dr Rose Smith (Research Fellow), Leeds University Business School

Social isolation and online learning during COVID-19, its impact on the language development of children that stammer and childhood and parental wellbeing

Following the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), the UK announced lockdown, resulting in enforced social isolation measures and a transition to online learning. Existing literature suggests that this may have had a significant impact on children in relation to their language development and mental health. Furthermore, some studies have suggested that parental wellbeing has also been considerably impacted by the continuing isolation measures. When considering this, it is important to also acknowledge the additional changes that COVID-19 has caused for parents of children with language impairments. This may include insufficient service support, increased economic burden and a lack of access to therapy.

Using online surveys, this study explores how social isolation and online learning have influenced childhood language development, childhood wellbeing and parental wellbeing. The main aim of the present project is to provide insight into how COVID-19 has affected both populations. Therefore, responses to these surveys will be analysed through comparing parents of children that stammer and parents of children with no known language impairment.

For more information please email Caitlin Heath Ps20ccah@leeds.ac.uk

Does sleep help children learn to read? (Hannah Nash and team)

When children first learn to read they sound out words letter by letter, but to become fluent readers they need to be able to recognise whole words. To do this, children need to build up a dictionary of sight-words in long-term memory via a process called orthographic learning.

When children first learn to read they sound out words letter by letter, but to become fluent readers they need to be able to recognise whole words. To do this, children need to build up a dictionary of sight-words in long-term memory via a process called orthographic learning.

Sleep has been shown to help consolidate orthographic learning in adults. Our research aims to investigate how and when words become part of the sight word dictionary in children and whether sleep plays a role.

For more information please email sleepandreading@leeds.ac.uk

Children Learning Adjectives (Cat Davies and Jamie Lingwood, 2018 – 2021)

Throughout 2019 we worked with around 100 families with children aged between three-and-a-half and four years old who took part in a study about how preschoolers understand sentences.

Research shows that adults use information about the world to interpret sentences quickly using adjectives. In this study, we showed that when given slower, clearer task materials, 3-year-olds can do the same thing. The paper reporting our findings is currently under review. A preprint can be found here..

The Paediatric ADHD Sleep Study – A study of sleep and its impact on the daytime functioning, cognitive development, academic attainment and wellbeing in children with ADHD (Anna Hamilton)

Around 5% of children have difficulty controlling their attention and behaviour; this is known as Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Children with ADHD are likely to do less well at school and experience later mental health problems. Furthermore, they often have sleep difficulties. Given that sleep is important for development and wellbeing, we are interested in the role that sleep difficulties play in the attention and behaviour problems that children with ADHD struggle with.

In our study we are looking to recruit a group of children with ADHD and a group of typically developing children of a similar age. We will see each child at two points in time, one year apart. The first time we see them we will measure the quality of their sleep using electrodes and by asking questions about their sleep habits. We will also measure the severity of their ADHD symptoms, daily activity levels, their behaviour, thinking skills, academic skills such as literacy and maths and their emotional wellbeing. The second time we see each child will we again ask them questions about their sleep and measure the severity of their ADHD symptoms, their behaviour, thinking skills, academic skills such as literacy and maths and their emotional wellbeing. We will then test whether the quality of their sleep at the first time point influences growth in the other measures over time. We are investigating the sleep difficulties children with ADHD face and what part they play in the attention and behaviour problems that children with ADHD struggle with. Knowing this, we can teach the parents of the children with ADHD ways in which to help their children get a better nights sleep.

What kinds of adjectives do children hear in child-directed speech during free play and shared book reading? (Cat Davies, Jamie Lingwood, and Sudha Arunachalam; 2018 – 2021)

We recently ran a series of studies measuring children’s experience of descriptive language during shared reading and during play. Although adjectives are essential for understanding and producing language, they can be difficult to acquire. Children must learn that an adjective refers only to part of an object, that a big mouse is quite different to a big house, as well as (in languages which put the adjective before the noun) having to remember the meaning of the adjective before they find out what it’s describing.

This study surveyed the kinds of adjectives that children hear in the language that adults speak to them, and tries to find out if these adjective types are helpful to children learning language. It tests the hypothesis that children hear lots of descriptive adjectives, i.e. those which describe things in their own right (e.g. ‘the handsome prince’), compared to contrastive adjectives, i.e. those which require them to make comparisons (e.g. ‘the big one’). Our findings suggest that children hear many more descriptive than contrastive adjectives in free play and during shared reading. This is the first stage in understanding the forms and functions of the adjectives that children are exposed to.

Davies, C., Lingwood, J. & Arunachalam, S. (2020) Adjective forms and functions in British English child-directed speech. Journal of Child Language, 47(1), pp. 159-185. Open Access https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/vjsfn

Features of child-directed speech used with children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (Rachael Staunton)

In the existing literature, correlations have been found between particular aspects of parental child-directed speech and the incidence of certain elements in their child’s speech, both in typical and atypical populations. Although in the autistic population, these relationships have not yet been identified as causal, more research is needed in this area to reaffirm existing findings, and further investigate the relationships between the language which parents use and the language which children with autism go on to develop. If causal relationships can be identified, it could have clinical and therapeutic applications for children with ASD.

This project focused on five aspects of the child-directed speech used by mothers with children with autism, compared to the CDS used with typically developing children. These were; use of pronouns such as he, she, and it; cognitive state terms such as think and know; terms used for self-reference, e.g. Mummy can help you, and diversity and density of verbs.

We found differences between the CDS used with typically vs. atypically developing children. Children with autism heard fewer terms such as Mummy used as self-referring expressions; they heard more what– questions; and heard a smaller range of verbs. However, the data was highly variable, with each parent’s patterns of usage varying considerably from others.

Our project highlighted the need for more robust investigations concerning the language environments of children with autism. Methodologically, it highlighted the importance of particular matching criteria when comparing children with autism with their typically developing peers. Rachael passed her viva in January 2019.

Can inferencing be trained via shared book reading? A randomised controlled trial of parents’ inference-eliciting questions on 4 year-olds’ oral inferencing ability (Cat Davies, Michelle McGillion and Danielle Matthews; 2015 – 2018)

Reading and listening comprehension involves lots of different skills. One of these is making links between different pieces of information in a story, or between information in a story and children’s own experiences. Making these links is called inferencing, and it is essential when children start to read independently. This randomised controlled trial investigated whether encouraging inferencing during reading helps children to understand what’s going on behind the scenes of the story. 100 families took part in this parent-delivered intervention over the course of a month.

(2019). Can inferencing be trained in preschoolers using shared book reading? A randomised controlled trial of parents’ inference-eliciting questions on oral inferencing ability. Journal of Child Language, 47(3), 655-679. doi:10.1017/S0305000919000801

With colleagues at the ESRC International Centre for Language and Communicative Development (LuCiD), we have created a range of resources aimed at parents, caregivers and early years practitioners to help support families with shared reading activities.

ManyBabies (Cat Davies with international collaborators; 2017 – 2019)

Throughout summer 2017, we worked with families with children aged 12 – 15 months on a project investigating children’s responses to different kinds of speech.

Research has shown that babies and young children pay more attention to speech with higher pitch and exaggerated intonation. This kind of speech is sometimes called child-directed speech, motherese, or baby talk. Evidence suggests that child-directed speech can help early language learning, e.g. by helping babies learn words and phrases, or by helping them realise that the speaker is talking to them, rather than to someone else in the room. The project aimed to understand the strength of this effect, how it might vary between babies, between languages and cultures, and how it might change as babies grow.

Together with babies from 68 labs worldwide, the final dataset of more than 2,700 infants is (to our knowledge) the largest experimental study of infant cognition ever! Results are currently being analysed and we hope to publish them early in 2019.

A follow-up study looking at the relationship between our original babies’ preferences for infant-directed speech and their vocabulary growth is currently under way. A huge thank you to all of our families who took part in these studies!

2020. Quantifying Sources of Variability in Infancy Research Using the Infant-Directed-Speech Preference. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 3(1), pp. 24-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919900809

Is bedtime the best time for shared storybook reading? (Anna Weighall and Hannah Nash)

Throughout summer 2017, we recruited families with children aged 3-4 years to take part in our project about the best time for parents to read to preschool children to help them learn new words. We would like to thank all the families who took part in our project.

Research has shown that school age children remember new spoken words better after a night’s sleep and that nursery age children remember more new words following a nap. We adapted this research so that it was more like real life, with parents reading stories to their children. We wanted to know when is the best time of the day for parents to read with their children to maximise their learning and memory for new words.

We provided parents with instructions and two story books and asked them to read one story before bedtime one week and then the other story in the morning the next week. Each story contained two novel words and after reading the stories we asked parents to see what their children had learned about the novel words.

We have now collected all of the data together and we are in the process of analysing it to see when is the best time to engage in shared storybook reading to promote vocabulary learning.

Look before you speak (Cat Davies and Helene Kreysa; 2014 – 2017)

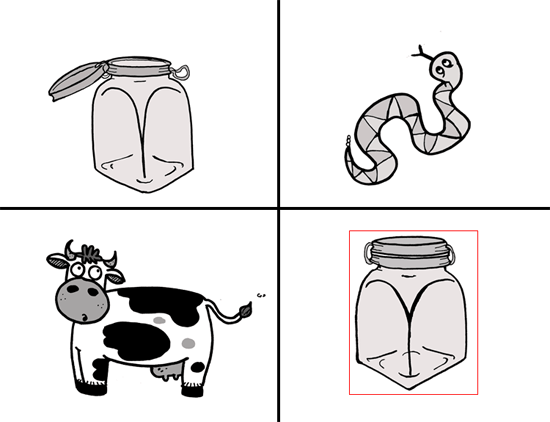

This study measured how much detail children give when describing objects for someone else. Our five year olds often missed out crucial information from their descriptions, e.g. ‘the jar’ to refer to a closed jar in the display to the left, whereas our seven year olds usually gave all the required detail. When we looked at the five year olds’ eye movements using an eye tracker, the fact that they looked at a contrast object (the open jar) or not didn’t affect whether they gave full descriptions. Amongst the seven year olds, the more they looked at the contrast object, the more informative their referring expressions were, just like adults. This study was published 2018 in the Journal of Child Language (preprint available via PsyArXiv).

Bilingual children’s semantic-pragmatic comprehension of quantifiers (Haifa Alatawi; 2014 – 2017)

My PhD thesis consisted of two novel studies. The first study explored the pragmatic abilities of English-Arabic bilingual and monolingual children in understanding quantifiers like ‘some’ and ‘most’, and how these related to the children’s cognitive abilities, particularly their executive functions. A bilingual advantage was found only on the pragmatic (not cognitive) tasks, although cognitive performance had strong effects on pragmatics. The second study aimed to establish how numbers and quantifiers are associated. It showed that children’s ability to produce sets representing numerical values had a significant effect on comprehension of ‘some’. I am currently preparing these results for publication.

Referential communication and executive function skills in bilingual children (Cecile De Cat and Ludovica Serratrice)

This experimental study focused on young bilingual children with unbalanced exposure to two languages.

It investigated (i) the relationship between executive function skills (cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control and working memory), socio-economic status and language experience, (ii) the impact of bilingual experience on proficiency in the language of schooling, and (iii) children’s ability to make referential choices appropriate to their listener’s information needs.

As part of that project, we designed an online calculator of bilingual language experience (based on a simplified version of the Utrecht Bilingual Language Exposure Calculator UBiLEC – Unsworth 2013), including a composite measure of language exposure and use (the BPI) which we used as a predictor in our analyses. Further information about the project, as well as the calculator, can be accessed by clicking on the project title above.

Overinformative children (Cat Davies, Napoleon Katsos, Clara Andrés Roqueta, and Courtenay Norbury; 2010 – 2015)

This set of studies investigated how children referred to objects on a screen; did they give enough information, just the right amount, or too much? When they listened to sentences, were they able to tell if a speaker was giving the right amount of information? We found that five year olds frequently underinformed, but were able to tell when their speakers were doing the same. We also ran this study with children with Specific Language Impairment, and found that they could also tell us when speakers were ‘misbehaving’ in the same way, though to a lesser extent than their typically developing peers. This work was published in Lingua (2010) and Journal of Experimental Child Psychology (2016).

Discourse competence in young children (Cecile De Cat)

This was experimental study of the discourse competence of preschool children. It demonstrated that the linguistic competence underlying the encoding of information is in place from at least 2;6 years of age. This includes the ability to identify and encode topics, and the use of definiteness and structural distinctions for reference establishment and maintenance. Children’s ‘errors’ were shown to be caused by cognitive (rather than linguistic) limitations.